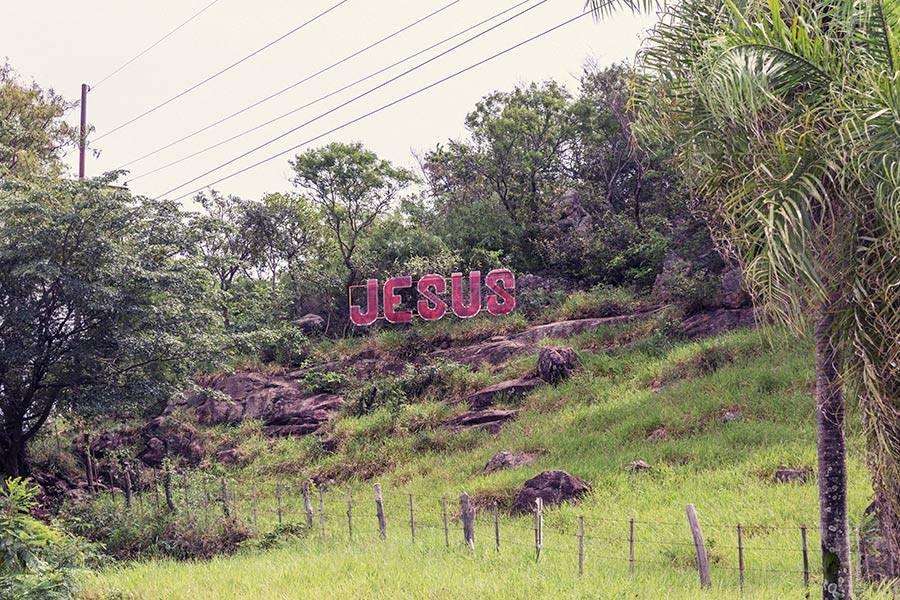

Not Hollywood

YEAR

2002

Ongoing

LOCATIONS

India, Vietnam, Italy, Serbia, Forida, Bosna Y Herzegovina, South Korea, France, Paraguay, Lebanon, Romania, Spain, UAE

Identity and landscape

Landscape has always been the engine of personal and collective identity creation because as individuals we tend to relate with the places where we grew up, regardless of their objective beauty: Rainer María Rilke (1875-1926) once said “The only country that man has is his childhood“. Just think of the feeling of belonging to the great empires, which historically have always been defined by their architecture – even urban planning – but also the pride of belonging that is created at various levels for the outskirts of contemporary cities, in which peoples’ origin is so exasperated to also affect local music and fashions. There’s pride for cities, but also for neigborhoods, and of course Nations.

As individuals we need to know who we are, which values we refer to, what’s the common plan: no matter the truth we need a coherent narrative of who we are to be able to relate (or not) with others, and politics has been able to ride this need in every periods of history.

Every empire was defined by its architectural specificities and each of them wanted to be unique in its aesthetic definitions, also to propagate the ideology of the time. The most visible modern legacies are dictatorial architectures of every nation that experienced such political framework, but also the precise canons of Egyptian, Greek, Roman, Inca, Khmer, Aztec empires. The styles of Teikan Yōshiki, Moghul, Renaissance, Byzantine, Gothic, Persian architecture didn’t happen by chance but they were created out of wider political plans and as every plan they lasted, died and were digested according to future political needs, together with every other example.

With globalisation and the establishment of a worldwide Neoliberal Ideology the style which has become the most known was emulative, a rush to appear as close as possible to the model of reference, its exotic propagation, an appropriation of it; in this context remixing symbols became the easiest way to glamorise places or concepts that have nothing to share with the symbol itself. It can be on purpose or by accident, but that’s the most powerful tool of identity making: as long as something looks like ‘us’ even if devoid of meaning, we can relate to it, it must be part of our time and welcome in ‘our’ ranks.

To build consensus is necessary to influence the perception of reality and the most effective way to do that is modifying landscape. Landscape is therefore a mirror of who we are, and vice versa; the narration of reality is more important than reality itself, both in politics and marketing: as long as there’s a coherent narration it’s difficult to feel alien to a specific ideology if you are born into it.

These remixed symbols should be welcome then, as they are the tangible proof we need in order to realise what is happening around us and why, as with their mere existence they let surface in front of us an ideology that is more difficult to frame and visualise, as its mechanics are way more spread, complex and geographically extended than in the past.