The Intimate Enemy

YEAR

2014-2017

EXHIBITED

Pelagica

LINZ FMR 19

LOCATIONS

Internet based

Digital Caliphate

The Intimate Enemy is a research project about digital landscape and contemporary forms of identity-building, focusing on internet-based propaganda of the Islamic State (Daesh) created or diffused by Isis fighters and supporters during the span of 3 years.

The work is an archive of over 1000 propaganda images dowloaded visiting social media accounts linked to the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq, since the declaration of birth of the Caliphate in 2014 and through 2017. Is geography still relevant in an interconnected and globalized world? How can citizens of incredibly different national contexts relate to each other through a careful branding process?

Normalization is a term that can very well summarize how identity is built: emphasizing familiar aesthetics and the use of a specific language – in this case web-based dialectic – can create relational identification between people, even while narrating a totally unexpected geographical context or committing unspeakable acts.

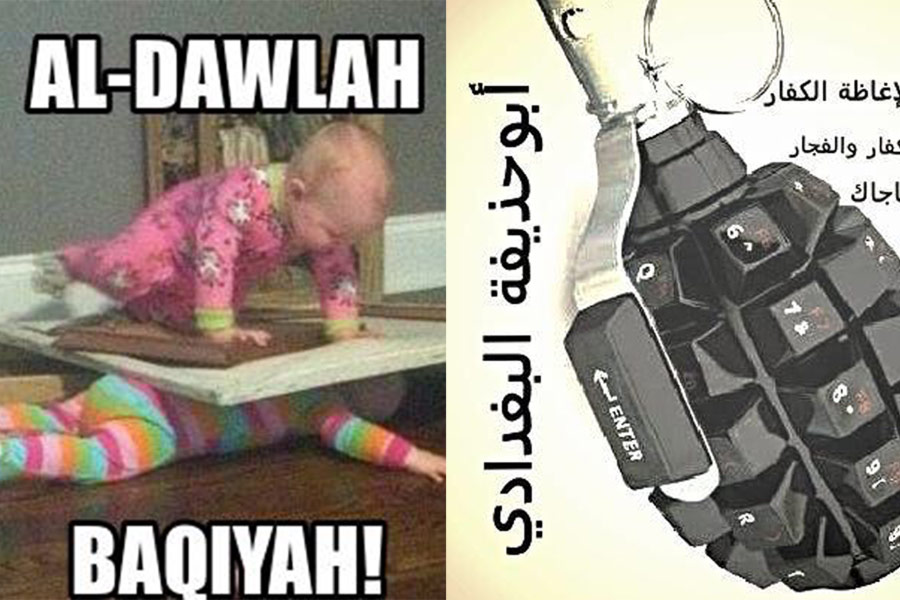

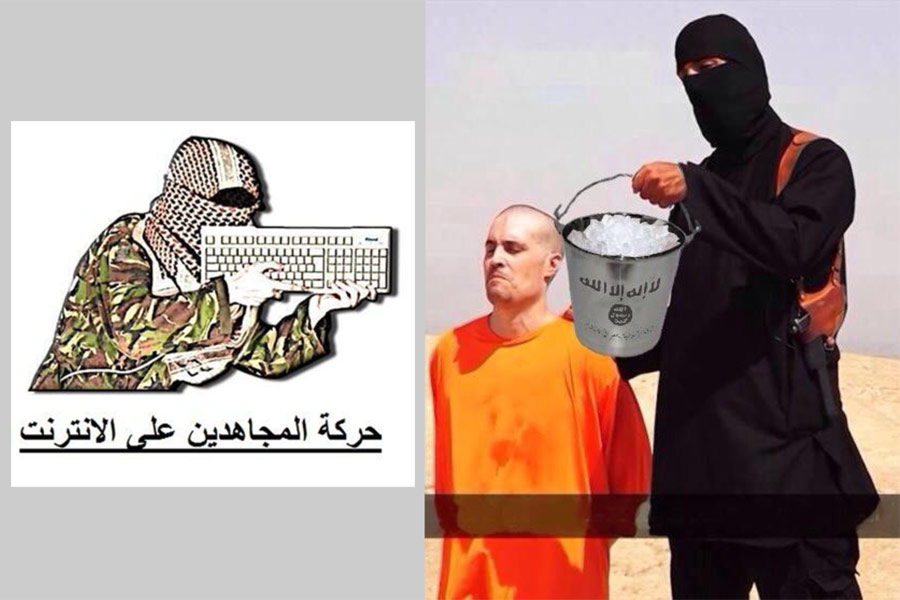

Avoiding violent scenes ‘The Intimate Enemy’ focuses on the typical aspects of the wider online dialectic such as memes, in this case created to troll enemies, ethnic minorities or the Iraqi central government, in attempts to normalize violence and expose Western hypocrisy to increase followers, and especially to foster appeal for potential international young jihadis, the most exposed demographic to inequalities generated by globalization.

Some images idolize the most famous commanders or foreign-fighters, others are mockery to western-media viral events like the ‘Ice bucket challenge’ or ridiculing of goods provided by the West and turned against it, like sized humvees and other military supplies provided by the USA to the Iraqi Army or various rebel groups; while Turkish Airlines is irreverently considered the official logistic sponsor bringing foreign fighters to the Caliphate, a smartphone very appreciated by Isis militias was even entitled the war-nickname ‘Samsung Al Galàxy’.

Portraits of martyrs are elaborated with the most popular manipulation softwares, excerpts from the Quran are dragged into different contexts to resonate with the Caliphate ideology, but there are also screenshots of material produced by official ISIS communication channels, and testimony of more elaborate campaigns such as exploiting internet’s most popular craze, cats, to reach the widest audience possible. Social media accounts such as ‘Cats of Isis’ were presenting cute pictures of fighters taking care of kittens found in villages after their conquest, as if inhabitants were not being slaughtered or displaced at the same time.

There is no proof of bots used to amplify tweets or shares count, but followers were often encouraged to have active role in propagating messages and were activated via coordinated ‘Twitterstorms’ aimed at modifying the perception of consensus of close contacts, giving the impression of a wider acceptance.

Creating borders to define the rules of duality is the only way to hold narrative power over a counterpart, and Isis practices of digital landscape colonization proved to be as powerful as its effort to invade countries to change geographic definitions.

The project is exhibited on phone screens available at gallery spaces or as a private network accessible via wifi routers installed at venues.