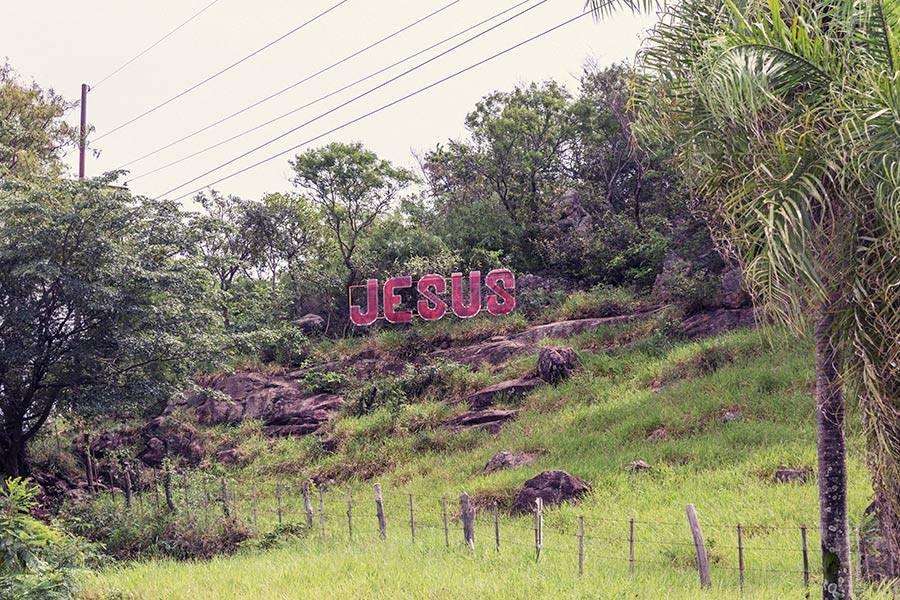

Not Hollywood

YEAR

2002

Ongoing

LOCATIONS

India, Vietnam, Italy, Serbia, Forida, Bosna Y Herzegovina, South Korea, France, Paraguay, Lebanon, Romania, Spain, UAE

Identity and landscape

Landscape has long been a driving force in the formation of both personal and collective identities. As individuals, we naturally connect with the places where we were born and raised, even if their aesthetic qualities do not objectively stand out. Rainer Maria Rilke, in his reflections on the concept of belonging, once stated, “The only country that man has is his childhood,” a sentiment that captures the essence of how place shapes identity (Rilke, 1926). In this context, identity is not only tied to geography but also to the emotional and psychological bonds we form with our surroundings. This phenomenon is not exclusive to rural or isolated landscapes, but also applies to urban environments. Historically, cities—especially those within great empires—have been defined not just by their politics and economies, but by their architecture and urban planning, which serve as reflections of power and collective pride. A similar attachment is observed in the outskirts and neighborhoods of contemporary cities, where local pride for specific areas is often as pronounced as national pride.

As individuals, our sense of self is intricately linked to our ability to define our identity within a broader collective framework. We seek a coherent narrative that ties together our values, history, and purpose. This narrative enables us to relate to others and navigate the complex political landscapes in which we exist. Politics, throughout history, has effectively harnessed this innate human need for belonging and identity construction. From ancient empires to modern states, political forces have shaped both the physical and symbolic landscapes in which identity is constructed.

Empires have always sought to define themselves through architecture, using distinct building styles and urban planning to propagate their ideological visions. This was true of the Egyptian, Roman, Greek, Inca, Khmer, and Aztec empires, all of which employed specific architectural canons to assert their power and uniqueness. Similarly, the imposing and monumental architecture of dictatorial regimes throughout history—such as the Fascist architecture of Mussolini’s Italy or Stalinist constructions in the Soviet Union—was designed to convey authority, control, and permanence. The aesthetic and architectural language of empires thus serves as both a reflection and a tool of political power, embodying the values and ideologies of the time. These architectural forms, though subject to change, continue to influence the cultural and political landscapes long after the empires that created them have fallen. As Anthony D. King suggests, architecture often represents “the political will of a society” (King, 1990), a tool of both historical and political memory.

With the advent of globalization and the widespread influence of neoliberal ideology, however, architectural and symbolic forms have become increasingly standardized and emulative. In the modern era, the dominant aesthetic is one of imitation and appropriation, as countries, cities, and corporations strive to align themselves with the perceived success and power associated with global centers of influence, particularly those of the Western world. The desire to emulate global standards of progress and prosperity has led to a homogenization of architectural forms, with cityscapes around the world increasingly resembling one another. This globalized style, often referred to as “global modernism,” is characterized by a rush to adopt Western architectural conventions and symbols, regardless of local context or meaning.

In this environment, the remixing of symbols has become a powerful tool for identity formation. The appropriation of images, signs, and symbols from different cultures or historical periods is no longer an incidental phenomenon; rather, it has become a strategic and deliberate practice aimed at reinforcing ideological narratives. As Jean Baudrillard argues, in the postmodern world, symbols are no longer tied to their original meanings but have become “simulacra” that circulate freely, detached from any original context (Baudrillard, 1981). In this sense, the very act of remixing symbols—whether consciously or unconsciously—becomes a mechanism for creating connections, however superficial or distorted, between people, places, and ideologies.

The most effective way to build consensus in a neoliberal world is to influence how reality is perceived. This is particularly evident in the ways landscape is modified—both physically and symbolically. Through architecture, urban planning, and the media, landscapes are shaped to reflect and reinforce specific ideologies. As David Harvey observes, the construction of space is never neutral; rather, it is inherently political, often serving to perpetuate the dominance of particular economic and social structures (Harvey, 2001). Landscape, then, is a mirror, reflecting not only who we are, but also the values and ideologies we subscribe to. The act of creating or altering a landscape—whether through the construction of new buildings or the manipulation of symbols—becomes a form of narrative control. In this sense, the landscape is a medium for storytelling, and the narratives it conveys are as powerful as the physical structures that populate it.

In the context of neoliberalism, the existence of remixed symbols—whether in the form of architecture, branding, or media—becomes an indicator of the ideological undercurrents shaping the world. These symbols, by virtue of their proliferation, reveal an underlying ideological narrative that is often difficult to frame or articulate. The global spread of neoliberalism, with its emphasis on market-driven development, consumption, and individualism, has created a world in which meaning and identity are increasingly fluid and malleable. The remixed symbols of neoliberalism, though seemingly disconnected from their original cultural contexts, nevertheless play a crucial role in shaping the collective imagination and fostering a sense of belonging. They allow us to relate to an ideology that is, in essence, global, omnipresent, and deeply embedded in our daily lives.

The study of landscape—whether through the lens of architecture, urbanism, or visual culture—offers a critical way to understand the ideological forces that shape our world. In the era of globalization, where landscapes are both literal and symbolic, the manipulation of space and symbols is an essential part of the ongoing process of identity-making. By critically engaging with these remixed symbols and landscapes, we can better understand the complex and often contradictory forces that shape our collective consciousness and, ultimately, our sense of self in a globalized world.